The Weight of Their Truths

By Anna Tan

Review of Bone Weight and Other Stories by Shih-Li Kow (Malaysia: Fixi Novo, 2023)

Boedi Widjaja - Installation view of Declaration of, Helwaser Gallery, New York (Sep 11 - Nov 7, 2019). L: 就是找不到往你的方向 (Can’t find my way to you), 2015. Archival print under diasec. R: 等著你回來 (Waiting for you), 2016. Graphite on paper. Courtesy of the gallery and the artist, photograph by Phoebe d’Heurle.

Image description: Two artworks are displayed on adjoining white walls in a gallery space. On the left, a picture features a close-up portrait of an individual wearing a cap that has a star on it. On the right, the picture, rendered entirely in black-and-white, depicts two elderly individuals facing each other. The figure on the left wears a hat and glasses, and he holds a rod. The figure on the right extends his left arm as if reaching out to shake the other’s hand.

According to my father’s Tong Shu almanac, heavy bones foretold a good life. They were dense with marrow and rich in celestial calcium, strong enough to weather hard knocks and march through life unmolested. Light-boned people, on the other hand, hovered on the edges of existence, insubstantial and easily broken.

—“Bone Weight”

In the titular story, the daughter of a fortune teller muses on the hypocrisy of her father’s profession while judging the fortune of the woman she’s trying to convince to accept her boss’s hush money. It’s telling, however, that the daughter is never named—the focus isn’t on her, though her thoughts frame the narrative. It’s Lakshmi’s plight that carries the story, the familiar one of a poor Indian woman standing up against a rich Malay man. It’s easy to see where the story will go.

Bone Weight and Other Stories strikes a very different tone from Shih-Li Kow’s first collection, Ripples and Other Stories (2008). There are similarities, of course: both have 25 stories based in Malaysia, both contain recurring characters over several stories, both speak about current events in Malaysia and both are inexplicably Malaysian. But where Ripples plays a lot with the way English is spoken by Malaysians, Bone Weight sounds more literary in an “international” kind of way. There are still hints of the local patois, but it’s subtler, a little more understated.

This is likely because of why the stories were written and where they were initially published. At the publisher’s launch party at the 2023 George Town Literary Festival, Kow mentioned that she started writing these stories during the pandemic, when she set herself the goal of getting 100 rejections per year for two years. An internet writing challenge that has been making the rounds in the past five years, it promotes the idea that focusing on quantity also increases the quality of the works produced. It’s also a quantifiable and achievable goal—a writer cannot control how many of their stories are accepted for publication, but receiving rejections is a mere numbers game. Need more rejections? Send out more stories. And because the writer is expecting to receive rejections, the exercise reduces both the fear and the sting of the depressing process of literary submissions.

Well, it worked—23 of these 25 stories were first published in international journals, with “Relative Distance” being shortlisted for the 2023 Commonwealth Short Story Prize. Has it changed Kow’s writing and the collection itself? Definitely. Where Ripples feels like it was carefully and purposefully crafted for an average Malaysian reader (only 3 of the 25 stories were first published elsewhere), Bone Weight is more experimental and spreads out over a wide range of styles. Story lengths vary from the very short (“Carrier” barely fills a page) to long (“Silica Dust, Silica Sky” is 22 pages long). There’s no primary genre, flitting from slice of life to science fiction to dystopic, even with a very myth-like tale (“Purnama”) making the cut. And while there are several recurring characters in clusters of stories, they’re not quite as involved or interconnected in the same way that Ripples was. I have to admit, I was a little disappointed by that.

Instead, Bone Weight and Other Stories is marinated in a sense of loss: of losing things; of heaviness and grief; of displacement, disenchantment, and disillusionment. Its meat is the displaced, the migrants, the people on the fringes, those who inhabit the in-between spaces. Many of the protagonists remain nameless—the people being written about, after all, are mostly nameless and invisible to society. The writing, whilst still beautiful, feels more formal, more distanced. Kow is no longer the aunty next door telling us about the lives and quirks of her friends and the people they meet down the road or at the market. Now, she is a distant observer jotting down the stories of the people we often overlook, dipping into their thoughts to create little moments of solidarity. Even the more light-hearted stories like “I Climb into a Book”, “Life Insurance”, and “Fried Rice” deal with loss in some form.

Boedi Widjaja - Installation view of Declaration of, Helwaser Gallery, New York (Sep 11 - Nov 7, 2019). L: 想著你回來 (Pining for you), 2019. Archival print on Awagami Kozo Thick White. R: 因為我的心中有你 (Keeping you in my heart), 2015. Archival print under diasec. Courtesy of the gallery and the artist, photograph by Phoebe d’Heurle.

Image description: Two artworks are displayed on white walls in a gallery space. In the background, black-and-white images of the side profile of the same elderly individual are displayed in a triptych. He has thick eyebrows and wrinkles, and he is subtly smiling. Each image shows his face with a slightly different expression and angle, as if capturing successive movements. The pictures are blurry and out of focus. In the foreground, an image captures the shadowy silhouette of a figure, against a dark rectangular frame.

On the whole, I preferred the longer stories in the collection. They’re hard hitting, leaving you with a sense of injustice, sorrow, or even a moment of empathy. When “Seventeenth Floor” ends with the protagonist wishing her mother had just said yes, there’s a flash of understanding that no, her mother will never visit; her mother never promises because she knows it won’t happen and she’d rather not lie.

Some of the shorter ones feel unfinished, as if I’ve been left hanging, waiting for an ending that will never come as the next story begins. Maybe that’s purposeful, to tell the reader that, like real life, not everything will have a resolution. Yet with some of them, instead of at least a vague sense of closure, I felt like I wasn’t quite sure what I was supposed to get from it.

Many of the themes that run through Bone Weight are perpetual hot topics in Malaysia, with an underlying sense of the hypocrisy of our society. “Old Enough for This” is the story of a girl married off by her father at fourteen; the call to ban child marriage has been brought up in Parliament countless times, but the law remains unchanged—Muslim girls under sixteen can be married with the approval of a Syariah court judge. Every five years, there is a loud and hopeful movement to vote in a better government, followed by a period of anger and disillusionment. But just like in “Under the Circumstances”, we complain about corruption at the highest levels while we flout the rules in our everyday lives and think nothing of slipping someone some duit kopi. We rage online about how America treats illegal immigrants and people of colour but turn a blind eye to the treatment of migrant workers, legal or illegal, and local Indians in Malaysia—themes that come up in stories like “The Fountain” and “Bone Weight”. “Relative Distance” and “Why I Say We’re Cousins” showcase the shifts in family relationships that are growing more complex, often pitting conservative Asian traditions against liberal contemporary ideas. Using AI in art is the newest talking point, with many Malaysians taking quite a lax stance on copyright—“It Only Amplifies” explores the use of a brain chip and how that alters the reception of art created under its influence. As far in the future as Kow takes some of the stories, the actions and reactions of her characters feel very familiar. We all know someone who would do that, say that, even as we shake our heads in despair.

Ultimately, it’s the women, named and unnamed, and their lack of freedom that hold my attention. The foreign women in “The Fountain” and “Waiting for Ghani” are desperately hoping to marry local men to legitimize their stay in Malaysia, searching for safety and permanence. Nain, the child bride in “Old Enough for This”, really isn’t old enough for it, no matter what her father and her husband say. Sofia in “Splice” is caught in a never-ending time loop of her daughter’s death, waiting for the insurance that fixes mistakes to actually fix the mistake. Similarly in “Life Insurance”, how much money must Shan keep pumping for updated policies to ensure her late mother is reborn when and where she wants to be? Lakshmi in “Bone Weight” refuses to be bought, no matter how hard Tuan Za’s staff tries to convince her that money makes all things right. Even in the middle-class Chinese household of “Golden Boys”, Mrs Chan’s choices are limited:

I toss an imaginary coin: heads grandchild or tails husband, mother or wife, wife or grandmother, cook or nanny, stay here or go there. The coin hovers in the air like a dragonfly, deciding where to land.

We never even learn her name, though all the men (and her daughter-in-law) are referred to by their names.

There’s a pervading heaviness in reading Bone Weight and Other Stories, a tired knowing that these are the lived experiences of many in the country I call home. Maybe it’s a reminder too that it’s not our call to judge others on their apparently bad choices or on the weight of their bones. Because despite luck, chance, fate, or choice, ultimately, money and the patriarchy still speak the loudest.

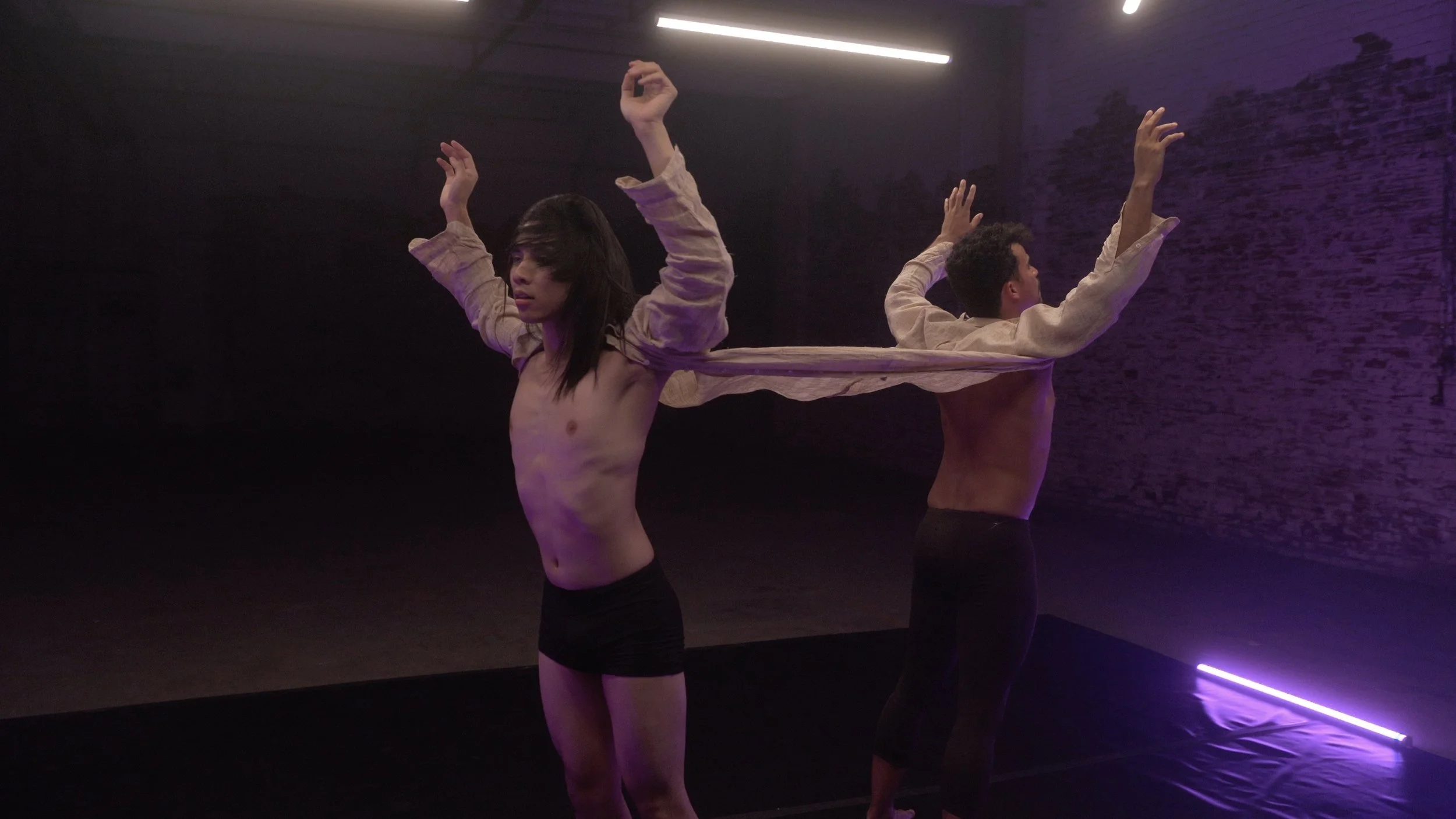

Boedi Widjaja - Installation view of Imaginary homeland: 我是不是該安靜的走開, Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film, Singapore (Jan 13 to 31, 2016). Courtesy of the artist, photograph by Cher Him.

Image description: A series of artworks are arranged on a white table. Various small, black-and-white portraits of individuals are displayed, most of which feature the figures’ faces and profiles prominently. Some portraits have pieces of thick, transparent, glass-like blocks laid over them.

Anna Tan grew up in Malaysia, the country that is not Singapore. She writes fantasy novels, puts together anthologies, and helps people publish books, which includes yelling at HTML for epub reasons. She also wrangles writers and deadlines for the Malaysian Writers Society and Penang Art District. Anna can be found tweeting as @natzers and forgetting to update annatsp.com.

*

Boedi Widjaja’s (b. 1975, Indonesia/Singapore) art contemplates on house, home and homeland through long-running, interdisciplinary series developed in parallel. Informed by the intercultural liminality of his migrant experience, his works span across diverse media, from drawing, experimental photography, and architectural installations to bio art, live art and film. Boedi’s projects have been presented in the Thailand Biennale (2023-24), FACT Liverpool (2021-22), Katonah Museum of Art, New York (2021), 6th Singapore Biennale (2019-20), 9th Asia Pacific Triennial (2018-19), and Diaspora Pavilion (Live Art program), 57th Venice Biennale (2017).

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

This Pride month, Ng Yi-Sheng reviews five queer comic titles bringing readers from the Philippines to Indonesia, Japan to Singapore, and to the USA.