#YISHREADS September 2023

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

I hear it’s National Hispanic Heritage Month! In the nation where our good editor is based, so I’m told. So I’ve dedicated late September’s column to works by Latino/Latina/Latinx/Latine authors, representing a range of nations, time periods and genres: Mexico/Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Cuba and the USA; 1899 to 2020; fantasy, science fiction, poetry, experimental novel and queer theory.

Sure, I’m a little sad I couldn’t include any Singaporeans and/or Southeast Asians in here—though I suppose I could’ve, since I’m friends with two Mexican writers based in this country: the children’s book author Adan Jimenez Alvarado and the theatremaker/academic Felipe Cervera. Maybe next time? Gotta get through my TBR list first!

Gods of Jade and Shadow, by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Del Rey, 2020

Inspired by the Maya myths of Xibalba in Popol Vuh, Moreno-Garcia’s woven a tale of a lowly 18-year-old girl, Casiopeia Tun, who accidentally releases a trapped death god, Hun-Kamé (known in most transliterations as One Death), and must journey across Mexico to retrieve missing fragments of his body and defeat his twin brother Vucub-Kamé (Seven Death), who’s usurped his throne. Across the course of the tale, Hun-Kamé grows more mortal and Casiopeia gains more godlike powers, while also discovering her own strength and beauty… yet also weakening physically from the curse of being linked to this god. And of course they fall in love. It’s a quest and a romance!

Something counter-intuitive is the choice of temporal setting: this isn’t set in the precolonial Maya world or conquistador Nueva España: it’s the Jazz Age, 1927 to be precise, which I suppose must’ve been a little easier to research and describe, plus possessing all the excitement of a society transitioning into modernity, flappers and champagne, Dolores del Río in Hollywood and Buster Keaton in Tijuana. Furthermore, the gods and mythical beings of the story aren’t fazed by modernity, but are shown to have carried on after conquest, adapting to fashions: the seductress Xtabay in an Art Deco apartment in the Condesa; the wizard Zavala running a Mayan hotel in lieu of a sacrificial pyramid. It’s a symbol of confidence in the representation of an indigenous civilization. Anglo archaeologists may say we’re fallen, but guess what? We never left.

I’m also reading this in the context of having first read the author’s later novel Mexican Gothic [i], which was quite different: a Gothic mystery with a much more self-assured and privileged protagonist, playing less with iconically Mexican tropes… but also a romance, also set in a vintage 20th-century Mexico stained by the shadows of earlier empires and colonialisms… and also notable for their agenda of forgiveness towards the inheritors of colonial privilege.

In both books, it’s a white man who commits the original sin—here, Casiopeia’s grandfather Cirilo, who traps Hun-Kamé. But the white descendants of this legacy do have a choice to reject violence: Casiopeia’s cousin Martín, who’s introduced as a bully, a brat and an absolute shit, later reveals himself (in chapters told from his POV) as weak-willed and unambitious but not a killer, refusing to allow Vukub-Kamé to make him a murderer… never completely redeeming himself, but justifying Casiopeia’s refusal to continue the cycle of violence, as long as she’s able to secure her own liberation.

Which is important for the reader to digest—often, we’re the oppressor, not the oppressed!

Dom Casmurro, by Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis

Translated by John Gledson

Oxford University Press, 1997

I’ve had this on my to-read list since I was an undergrad, reading The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas, another novel by this famed 19th century Brazilian author. First published in 1899, this book is known as his masterpiece: an inversion of the classic realist novel, inspired by Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy.

Surprisingly, though, this is a super-easy read, quite unshocking to the 21st century reader in its experimentalism. The narrator, Bento, comments on his process of writing, addressing the imagined lady reader in between her visits to the opera, apologising for his poor memory of his youth in the 1850s, going into fantasies about a visit from the Emperor Pedro II to persuade his mother not to send him to the seminary, confessing his bad habit of promising 1,000 prayers to God if he’ll change the weather… and most fundamentally, being a pathetic and neurotic mess of a first-person narrator. It’s all pretty common now, but it’s kinda amazing to see it was done before literary modernism was even a thing.

What captures the attention more is the weird way Brazil’s past—specifically, slavery—is invoked. Machado de Assis, as a half-Black man of the middle classes, has chosen to write about an upper-class slave-owning family, and while they’re hardly portrayed as paragons of dignity and virtue, they’re never shown as monsters, while their slaves and the working-class Black folks selling candies in the street speak in a cringy pidgin, never expressing any resistance to the system. The intro explains that the colonial 1850s were radically different from the modernising 1890s, a fact underscored by Bento’s widowed mother trying to look older than she is, going around in old-fashioned clothes in an antique chaise. The mentions of slavery may be a nod to how underdeveloped Rio de Janeiro was at the time, not any commentary on race. (Or were lots of other novels of the era as casual about it as this is? This is the kinda thing I wish Gledson’s explanatory intro would explain!)

Trafalgar, by Angélica Gorodischer

Translated by Amalia Gladhart

Penguin Classics Science Fiction, 2020

A 1979 collection of sci-fi stories by a major Argentinean author of spec fic—but they're all interlinked, focussed on the titular character, so we might as well call it a novel? The sci-fi bit is debatable too: the back blurb argues that the stories could just as well be classified as magical realism.

You see, our hero, Trafalgar Medrano of Rosario (Gorodischer's home city) is an interplanetary salesman, making epic voyages to polysyllabic star systems in his clunker of a spaceship. Yet unlike, say, the contemporaneous Star Wars and Star Trek, the worlds he visits aren't populated by green-skinned insectoids. Everyone's perfectly human, usually able to communicate with him in Spanish, willing to barter and trade perfectly standard goods like comic books and costume jewelry and tractors. There's the odd reference to a high-tech global shield to keep the deadly effects of the sun out, and strangely named foods and peoples and weapons. But the main differences between them and 20th-century humanity are in social organisation—the rigid caste system of Serprabel; the listless tribes of Anandaha-A that do nothing of note except when they erupt into dance; the ultra-conservativism of Gonzwaledworkamenjkaleidos, where modernity is held back by the fact that one's ancestors never die.

Adding an extra layer to all this is the fact that the story's told from the POV of a writer in Rosario named Isabel who meets Trafalgar in the pub and makes him coffee—she never gets to accompany him on his odysseys, nor does she aspire to, being comfortably middle-class with a husband and a kid and a cat—though she still hungers to hear what may well be simply tall tales. (One story, "Trafalgar and Josefina", is told third-hand, via an aunt who bumps into Trafalgar at the bar.)

It's unexpected from a feminist writer (according to Wikipedia!), since Trafalgar is in many ways your prototypical MCP, swashbuckling, pulp hero, seeking out a new woman to boink on every sphere. And there's no overt critique of his behaviour; rather, there's some admiration for what he'll do for his romantic flings, and admiration for the women themselves, who're often larger than life: an anthropologist slowly going mad, a guest-house worker sick of her husband who keeps coming back from the dead, the tyrannical matriarchs of Veroboar, a fugitive queen with a gun... and eventually Trafalgar's own precocious daughter Eritrea (also named after a battlefield), and indeed, the narrator's own aunt.

And back to the topic of sci-fi: there are stories which deal with time and the nature of reality, echoing Borges: a planet almost identical to Earth 500 years ago in the past where Medrano is able to ferry Columbus to the Americas in his spaceship; a planet where one wakes up in a different period of time every morning; a planet of boring, literal-minded people where only a single lunatic perceives a deeper reality than our own. The narrator shudders, then makes more coffee.

Which is, I suppose, characteristic of what you can do when you're in a country which isn't the centre of global civilisation; where you're not even living in the capital of your own country. You don't seek to subject other worlds to your vision; you just seek to make a living off what you can barter. If you change history, who'll remember it? Who'll even believe you? and maybe you never leave at all. You just sit and write in the margins, happy to hear another story.

Yoruba from Cuba: Selected Poems by Nicolás Guillén

Translated by Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres

Peepal Tree, 2004

I'd previously read bits of this iconic Afro-Cuban poet in Spanish class, so it was a delight to encounter a bilingual volume of his work, covering his published career from 1931 to 1972, tracing the manifold ways he explored Black, pan-American and leftist politics.

Here we've got elegies for Che Guevara, Federico García Lorca, Emmett Till and MLK; pleas for soldiers to recognise their brotherhood with the people they're killing; reclamations of the Afro-Cuban dance called the son; addresses to cities (Kingston, New York, Panamá, Madrid); even an outrageous imaginary newspaper listing of white people on sale as slaves and a cringy dramatic poem in which four little Cuban boys—white, Black, Chinese and Jewish—squabble with each other and have to be reminded by the white (!?!) mother that the same blood runs in all their flesh.

Quite a splendid survey, portraying how an intellectual of the global South need not be parochial, responding to shifts in world affairs, never shying away from the glory of anger and sensuousness. I've still got a soft spot for his early works, inspired by Santería traditions, shocking the Black elite of his times with their embrace of the working-class, Black, vernacular voice—I read half of "Sensemayá" aloud to my three-year-old twin nephews, and they laughed in delight at its rhythmic repetitiveness and dramatic violence. (It is, in fact, written as a charm to kill a snake.) But also his later work: "Balada", recalling the anguish of his enslaved heritage in "I Came on a Slave Ship"; mourning the newly fallen in war in "Ballad". What a voice.

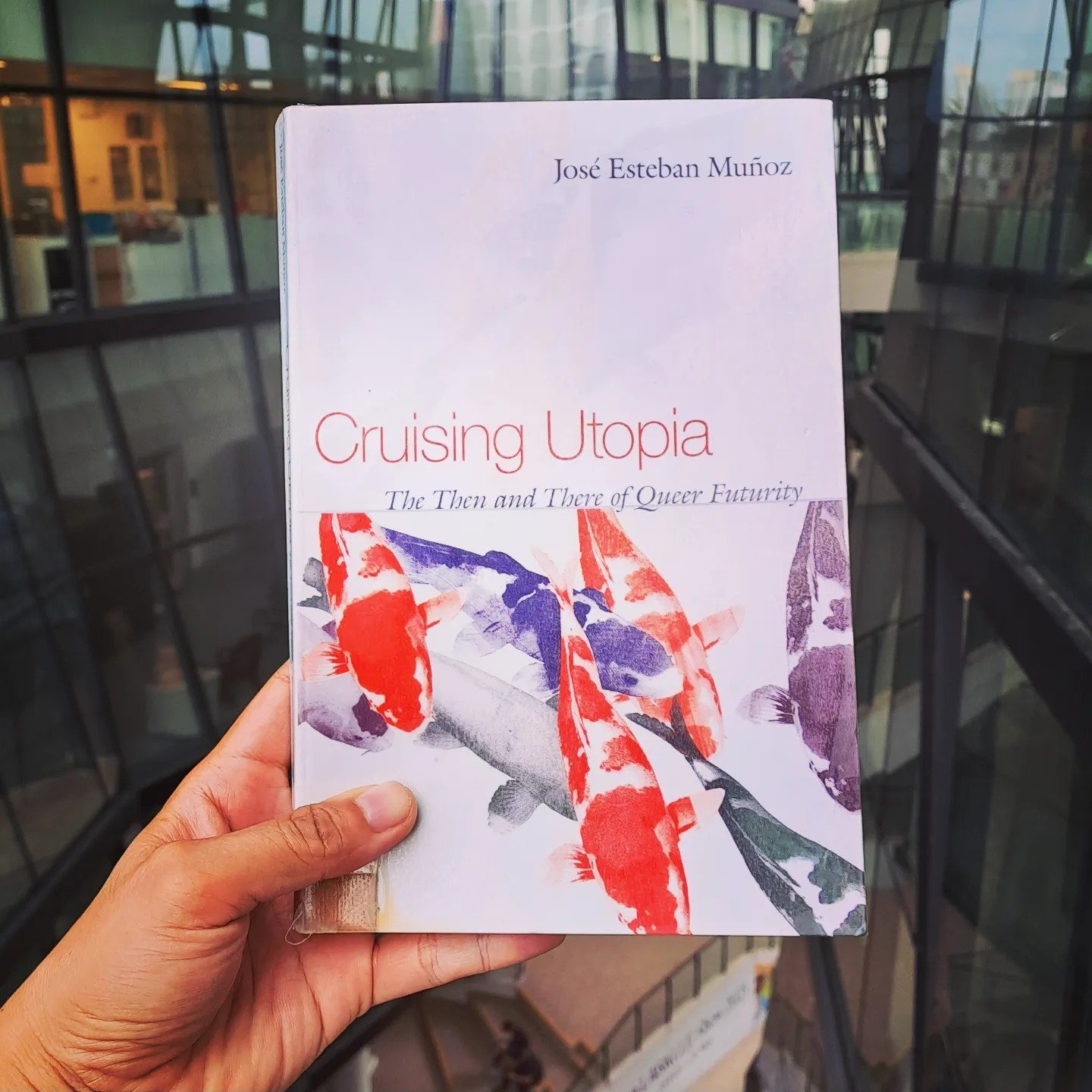

Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, by José Esteban Muñoz

NYU Press, 2009

Finally got round to reading this classic of queer theory! And what a soulful journey it is, maybe especially because I lived in New York at roughly the same time as the late author, party to the debates about homonormativity and Rudy Giuliani’s scorched-earth clean-up of queer nightlife, also flinching at the white-centred beauty standards of bars like G.A.Y. (though my ethnic refuge was the Asian club The Web).

The work’s principally a rejection of what the author calls gay pragmatic thought: the assimilationism of Evan Wolfson and Andrew Sullivan that would have queer people aspire to fully participate in straight culture—gay marriage and the overturning of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell—rather than participating in and dreaming of an idealistic alternative. He’s drawing from Lee Edelman and Leo Bersani’s more pessimistic outlooks on gay culture (e.g. “Is the Rectum a Grave?”), but refusing despair, understanding utopia not as a KPI-road-mapped future but an imagined state (apparently influenced by the idealism of Ernst Bloch, whom I’ve only vaguely heard of).

He’s taking inspiration from avant-garde art: the sexual memoirs of Samuel Delany and John Giorno (beholding an orgy makes you realise you’re not a perverted individual but part of a community!), the ephemeral dance gestures of Kevin Aviance and Fred Herko, the forgotten early plays of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka, the art of Andy Warhol, the poetry of Frank O’Hara and Elizabeth Bishop, with all their expressions of queer failure—is the art of losing indeed not that hard to master?—and queer virtuosity. Also his own lived experience as a Cuban-American son of immigrants—both Castro’s revolution and the gay revolution as failures—disciplining his effeminacy through machismo, finding refuge in punk, knowing that mainstream queerness, even the idealised, old-school, sexual economy of anonymous sex in subway station toilets and the piers, full of its own body hierarchies, was never made for guys who look like him.

Yep, I can identify with that. And also the constant hope, the constant seeking of other possible worlds, through the misremembered past or a tinted lens on the present. Better fantasy than despair. Better fantasy than compromise for the present.

Endnotes

[i] My review of Mexican Gothic appears in #YISHREADS October 2022, here: https://singaporeunbound.org/suspect-journal/2022/10/28/yishreads-october-2022

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

This Pride month, Ng Yi-Sheng reviews five queer comic titles bringing readers from the Philippines to Indonesia, Japan to Singapore, and to the USA.