My Book of the Year 2023

-

Mentions of war brutality, torture, and sexual assault.

SUSPECT is pleased to share with you this year’s favorite reads recommended by 26 Singaporean writers, artists, and thinkers and by the Singapore Unbound team. The recommended book does not have to be written by a Singaporean, but if it isn’t, contributors could recommend a second title that is by a Singaporean.

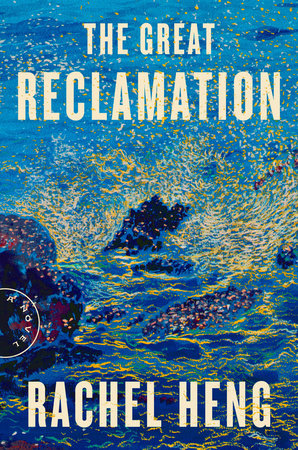

Acclaimed by a number of contributors as the Great Singapore Novel, Rachel Heng’s The Great Reclamation is praised for its sweeping historical scope and intensely intimate emotions. If you’d like to hear Rachel read from her novel, please join us for our Second Saturdays Reading Series Celebration and Fundraiser (https://www.eventbrite.com/e/129-second-saturdays-reading-series-gina-apostol-and-rachel-heng-tickets-756211136867) on December 9 in NYC.

Besides fiction, poetry and non-fiction have also received enthusiastic endorsements below. As novelist Daryl Qilin Yam puts it, 2023 has been “a hallmark year for Singapore literature.” No wonder, since we all turn to literature to help us make sense of the tragedies around us.

Our grateful thanks to our contributors! We hope you enjoy reading all the contributions as much we’ve enjoyed compiling them. Please support independent publishers and booksellers by ordering from them directly. If you believe in intellectual and cultural exchange as we do, please consider making a donation here (https://fundraising.fracturedatlas.org/singapore-unbound/campaigns/5992).

Ann Ang, writer and literary researcher. 2023 has turned out to be a year with a signal number of books examining Singapore's recent past, especially in between the immediate postwar period and the seventies—the last decade before the Singapore of today became recognisable in all aspects: its built landscape, ecologies, social institutions, and self-made myths. The Great Reclamation by Rachel Heng (Penguin Random House, 2023) is an important book for depicting the political agitation of the fifties, and the move into public housing, from a sympathetic, accessible perspective that pits the romance of today's nationalising narratives against dissenting voices from the past. The recently launched historical picture-book, Once Upon an Island: Images of Singapore (1950-1980) (Suntree Media) a combined effort by the Polunin family to select 1000 images from Dr. Ivan Polunin's films, provides an excellent non-fiction companion to this period, with aerial images and portraits of everyday people on the streets. But my book of the year is reserved for a title that is only half-Singapore: The Second Link: An Anthology of Malaysian and Singapore Writing, edited by Daryl Lim Wei Jie, Hamid Roslan, Melizarani T. Selva and William Tham (Marshall Cavendish, 2023), in which Malaysian and Singapore writers come together to examine a shared, fraught history, with many fiction and non-fiction pieces speaking powerfully about how Singaporeans were once Malayan. It's a sign that Singapore now recognises itself better, having learned to live with a fuller range of histories.

Anthony Waugh Koh, bookseller. Shoji Morimoto is phenomenally popular in Japan. This guy is deep; social media have only scratched the surface of his mind. In a society that values a proper job and productivity, Morimoto’s philosophy of work will amaze you. If you’re unhappy at work, Rental Person Who Does Nothing (Picador, 2023) might just renew your hope in trying something new or even unusual.

Balli Kaur Jaswal, novelist. Prasanthi Ram's Nine Yard Sarees (Ethos Books, 2023) is my book recommendation. In her debut book, Prasanthi weaves together the lives and stories of a Tamil diaspora family. Her prose is sharp and incisive without sacrificing the warmth and nostalgia of childhood, family gatherings, and heartbreak. A rich addition to the Singlit canon. I'm excited to see what Prasanthi writes next.

Cyril Wong, poet and fictionist. The Campbell Gardens Ladies' Swimming Class by Vrushali Junnarkar (Epigram Books, 2023) is a novel many will underestimate, but it possesses an honesty, vulnerability and clarity of expression or storytelling that is becoming less valued by "literary fiction" over time. For an interconnected group of women living in a condominium, swimming becomes not just a metaphor for cultural adaptation and survival, but also for personal freedom, transcendence and even redemption in this heart-warming novel.

Damon Chua, playwright. One of the best non-fiction books I have ever read is Hua Hsu’s Stay True (Vintage Books, 2022), a moving and lustrous account of a friendship between two very different Asian American undergraduates at UC Berkeley in the 1990s, a friendship that ended when one of them met an unexpected end. This is a story about a specific place and time when everything seemed possible, when the guilelessness of youth opened the door to great music, raucous joyrides, and endless summers. Most of all, this is a portrayal of how intimate a platonic relationship can be, despite the passage of time and the loss of innocence. In contrast, Kirstin Chen’s Counterfeit (William Morrow, 2022) is at once light-hearted, vivacious, and wryly satirical. Designed to be consumed in one gulp on a cold winter’s night, this is the story of two Asian women who join forces to create a business around fake designer handbags. Chen goes deep into the creation of such counterfeits, with different levels of quality and similitude, some even fooling the experts. The book hits its stride when dealing with the relationship between the two women, showing how the promise of the “American Dream” is never too far from the temptation of criminality.

Daryl Lim Wei Jie, poet, editor, and translator. He Who is Made Lord: Empire, Class and Race in Postwar Singapore (ISEAS Publishing, 2023), by Muhammad Suhail Mohamed Yazid, is a fascinating study of a transitional institution often overlooked: the Yang di-Pertuan Negara, established in 1959, a precursor to Singapore's current Presidency. Muhammad Suhail brings out the inherent tensions in setting up this institution: its positioning as a decolonial gesture amidst colonial realities; its significance as both a Malay and Malayan icon; its politically apolitical (or is it apolitically political?) nature. A very timely read considering Singapore just held its presidential election this year, for an institution (the Elected Presidency) that continues to evolve and mean many things to many people. On the poetic front, Boey Kim Cheng's The Singer and Other Poems (Cordite Books, 2022) is a collection to be carried away with. One is led on by his beguiling, restless, sweetly melancholic voice -- toward adventure, toward rapture, towards perhaps, at last, a kind of stillness.

Daryl Qilin Yam, novelist and arts organizer. 2023 for me has been a hallmark year for Singapore literature. I can't recall the last time I read so many consistently good offerings from Singapore authors, such as Balli Kaur Jaswal's homecoming novel, Now You See Us; Kirsten Han's gutting memoir The Singapore I Recognise; and Tse Hao Guang's The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association, a poetry collection that is in many ways experimental, yes, but utterly and keenly heartfelt. Nonetheless, two books stand out to me as ones for the ages, books that so happen to touch upon our coastlines. The first is Rachel Heng's The Great Reclamation (Riverhead Books, 2023), a novel that thoroughly deserves the moniker of the Great Singapore Novel, astonishing in its scope and yet utterly intimate in its details, with a plot that is at first wondrously luxuriant in its pace before it is allowed to gallop fittingly vis-a-vis the growth spurt of its characters and the worlds they inhabit. My second pick is Cyril Wong's Beachlight (Seagull Books, 2023), a lush experience from start to finish, deploying words and phrases I'd never seen the poet use before – and he has written plenty at this point, haha! I really could have read 20 to 30 pages more of this book-length poem, and thought to myself how endlessly fine it would be to forever float on this rumination on the primordial, and the primal desires that continue to link us all to one another. His craft is a craft that keeps on giving.

E. K. Tan, literary scholar. I don't think I can choose one book to be my book of the year. So instead, I will share a book that I have read recently by Feng-mei Heberer. Asians on Demand: Mediating Race in Video Art and Activism (University of Minnesota Press, 2023) is a tribute to those activist cultural workers who have used their art “to challenge oppressive institutional structures of racism, classism, sexism, and homophobia” (1–2). I find the double-entendre invoked by the title “Asians on Demand” witty and evocative. On the one hand, Asians “on demand” speak to the accessibility of Asian representations and Asian media contents with the rapid growing popularity of video streaming services around the world; on the other hand, it questions how this growing global culture of media consumption continue to perpetuate the kind of Asia stereotypes by enabling neoliberal discourses and narratives to exploit Asian representation for the promotion of liberal multiculturalism of minority inclusivity. This is a book about the continuous struggle of Asians in navigating their presence in global media.

Felix Cheong, poet and fiction writer. Routes 2: A Singaporean Memoir 1976-2000, by Robert Yeo. Twelve years in the making, playwright-poet Robert Yeo’s follow-up to Routes: A Singaporean Memoir 1940-75 is finally out. Like the first volume, two things stand out for me. First, how meticulously he keeps notes over the years, so that even one-off meetings are replete with details. Take, for instance, his description of American poet Robert Creeley, who visited Yeo at his home in 1976. Yeo also reproduces correspondences, newspaper articles and creative works he has saved over the years, creating a pastiche that stitches up the patchwork we call memory. And, unlike other memoirs that view the world narrowly through their authors’ lens, Yeo always frames his narrative against socio-cultural-political developments, so that his story is as much the country’s. The second thing that strikes me is how much of a mover and shaker Yeo was in the 1970s and 80s, and how embedded he was in the literary ecosystem. For instance, he was the editor who had seen the potential in Catherine Lim’s short stories and encouraged her to publish them in a volume, Little Ironies. Yeo was also the chair of the Drama Advisory Committee that approved the scripts of theatre company Third Stage, later fingered by the government for being part of a Marxist conspiracy in 1987. Yeo candidly admits that the “fear factor” had initially gotten the better of him when Tan Kheng Sun, husband of playwright Wong Souk Yee – one of those detained by the Internal Security Department – had approached him to write a letter stating her plays had, in fact, been approved for performance. Yeo eventually did, but he was sure his letter “made no impact at all”. Routes 2 makes for a fascinating read, not just for its portrait of the writer as a middle-age man navigating fatherhood, career and writing, but is revealing of how even though times have changed, the Singapore authorities’ tight leash on artists hasn’t.

Hamid Roslan, poet. My friends will know that I’ve been speaking to no end about Rachel Cusk, which is why I’m recommending her latest, Second Place (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021). She might be my favourite novelist right now. The way she goes about writing her novels, as conversations, delights me to no end, because they appear to me like the true shape of a story.

Tse Hao Guang, poet and editor. In a year of several noteworthy books, I nominate Daryl Li's debut The Inventors. It a rare collection of essays amidst the poetry and novels, and the first originally English book from its publisher Trendlit. But most importantly, it wrings art out of particularly Singaporean anxieties and neuroses. Here's the blurb I wrote for it in full: “Mediocre curry; a re-gifted book languishing in a secondhand bookstore; stolen orchids; a procession of fictional diseases. Li makes an alluring, haunting book out of such “mismatched moments”, out of the ways we disappoint ourselves and each other. This is the kind of failure we should all aspire to.” I want to mention several other reads which doubtless will reappear on this list: Rachel Heng's The Great Reclamation, one of the most ambitious Singapore novels of recent years; and Cyril Wong's latest collection Beachlight, which reaffirms his place as Singapore's foremost exponent of the book-length poem. I should also recommend Wong May's A Bad Girl's Book of Animals, reissued this year and frontrunner for my Book of the Year 1969.

Jason Soo, filmmaker. "Bodies piled on top of each other – mutilated bodies, with arms chopped off – bloated decaying bodies that had obviously died a day or two before. Bodies whose limbs were still tied to bits of wires, and bodies which bore marks of having been beaten up before their murder. Bodies of children – little girls and boys – and women and old men. Some bodies lay in blood that was still red, others in pools of brownish black fluid. Bodies of women with clothes removed, but too mutilated to tell whether they were sexually assaulted or just tortured to death." From Beirut to Jerusalem (The Other Press Sdn. Bhd., 2023) is a raw and unflinching account of Dr. Ang Swee Chai's work in the refugee camps of Lebanon and Palestine. First published in 1989, the book has been updated with a new introduction, addendum and postscript. It has also been translated into Mandarin. Dr. Ang witnessed the massacres at Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, where the death toll was estimated at around 3,000 Palestinian refugees. As I write these words, the death toll in Gaza has surpassed 11,500. By the time you read this, the only question is how much higher. The killing machines of Israel has spawned a new acronym - WCNSF - wounded child, no surviving family. This acronym bears repetition. Read it a few times, until you digest its full consequences: Wounded Child, No Surviving Family. Palestinians are writing their names on their own limbs, in case there's no one left to identify them when they die. What is the world waiting for? And what can I do, I'm only one person, said 7 billion people. Talk to your friends. Take part in the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement. The extent of Singapore's involvement in the Israeli arms trade will shock you (dimse.info/singapore/). Ask your members of Parliament why our tax money is being used to fund and invest in the Israeli military industry, which uses Gaza and the West Bank as a killing laboratory. And don't stop talking even when there is ceasefire, because it didn't start with Hamas on October 7. It started with our British colonial masters and the Balfour Declaration in 1917, with the Nakba and the formation of Israel in 1948, with apartheid and the settler-colonization of Palestine in 1967, and with the siege and blockade of Gaza in 2007. These four events are the root causes of the carnage that is going on, and will continue to go on until the international community forces Israel and its supporters to take responsibility for the carnage they have unleashed. Do not stop talking even when there is ceasefire. Do not stop talking until Palestine is truly free.

Jeremy Tiang, writer and translator. For many years now, Kirsten Han has been an essential voice with her journalism and her activism on issues such as abolishing the death penalty and migrant workers’ rights. This is particularly important in Singapore, a landscape where challenges to the dominant narrative can be difficult to find. Han's essay collection The Singapore I Recognise (Ethos Books, 2023) is the culmination of her longstanding work, cutting through establishment orthodoxies to lay out a clear, radical vision of what a more inclusive Singapore could look like. Speaking of challenging dominant narratives, I'd also recommend Rachel Heng's The Great Reclamation (Riverhead Books, 2023), a revisiting of Singapore's origin story that asks whether the price we paid in the name of progress has been worth it.

Joanne Leow, literary scholar and writer. My book of the year is the late and dear Y-Dang Troeung’s gut-wrenching memoir Landbridge (Alchemy Press, 2023). A Cambodian refugee by birth and a brilliant critical refugee studies scholar, Y-Dang’s life was cut short in 2022 after a terminal illness. Her last months were spent writing this book that is part memoir, part epistolary, and part keenly felt reflections on life as a refugee in Canada and inter-generational trauma. Her courage and love are palpable in all the pages. Her letters to the young child she leaves behind are wise and proleptic. There is no more urgent read in these times of terrible violence and loss. My Singaporean book of the year Balli Kaur Jaswal’s Now You See Us (Harper Collins, 2023). I have been teaching this incisive page-turner of a book in my university class in Vancouver and it has been pulling the students in at every turn. Balli’s lovingly rendered Filipina domestic worker characters are deeply believable. Their hard-won perspectives offer us troubling yet unsurprising insights into the horrors of the migrant labour experience in Singapore. The book is engaging and immersive, even as there are so many profoundly recognizable moments and characters in this book that should bring us to shame.

Jolene Tan, novelist. My nomination is Eliot Higgins' We are Bellingcat: An Intelligence Agency for the People (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022). Higgins details the history of this extraordinary initiative, which sees ordinary people search collaboratively for the truth about major events, such as the 2018 Skripal poisoning and the chemical weapon attacks by the Assad regime against Syrians. It is a reminder of the liberatory and democratising promise of the internet and social networks, and a testament to the value of honesty, restraint, and a simple dedication to doing good work. Invaluable at a time when information pollution and ideological dogma seem to have grip on much of public life.

Jon Gresham, fiction writer and photographer. There are no easy answers adequately addressing peoples’ place in the natural world. My book of the year is the Arthur C Clarke Award winning dystopian, Australian novel, The Animals in That Country (Scribe US, 2022) by Laura Jean McKay. Prophetic and disturbing in its vision, this novel tells the story of a flu pandemic that allows people to understand and talk with animals. A wildlife guide, Jean takes a road trip to find her abducted granddaughter. In The Animals in That Country people are overwhelmed by the harshness, innocence, cruelty, and playfulness of animal voices. The novel ‘repositions the boundaries of science fiction’ and explores consciousness, language, empathy and connection with animals without idealising or romanticising. My Singapore book of the year is Raffles' Banded Langur: The Elusive Monkey Of Singapore And Malaysia by Dr. Andie Ang and Sabrina Jaffar (World Scientific, 2022). What would they say if they could speak?"

Yeow Kai Chai, poet. Two poetry books have kept me awake these past months: Tse Hao Guang’s The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association (Tinfish Press, 2022) and Koh Jee Leong’s Inspector Inspector (Carcanet, 2022). Both titles may seem chalk and cheese, but they share one thing in common – the bravery to draw on legacy and find something new and fresh. Hao Guang’s left turn into experimentation pays off with some of SingLit’s zaniest lines ever. He toys with cultural baggage without proselytising in poems such as ‘Is Chinatown your eternal burden? Limitless like the universe?”, turning aphorisms on their head and playing with spacing, enjambement and semantics in freewheeling ways. There’re ghosts of Marianne Moore and e. e. cummings, but transposed into the 21st-century Asian hyperrealist metropolis. With these so-called calligraphic poems, he’s exuding a sense of freedom and unself-seriousness rarely seen these days, somehow managing to bypass the usual-by-now virtue-signalling and venturing into new ways of connection. Jee Leong, likewise, has accomplished a feat few Singaporean writers do – talk about one’s parents without either being sappy or angsty. He does a form of lyrical séance with a series of magisterial palinodes dedicated to his late father, retracting sentiments the latter had expressed when alive. The taciturn, industrious paternal figure is reconstituted ingeniously – every word, perfectly placed, draws blood.

Kirsten Han, journalist and editor. A book that I enjoyed reading this year was This Is Not A Book About Benedict Cumberbatch, by Tabitha Carvan (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2022). It really resonated a lot as I read it, in the way that it articulated the fun of being a fan, of having a hobby and finding something that just really evokes joy. I had many 'hard relate' moments and this was a book that I thought about even as I wrote my own essay on embracing K-pop as a coping mechanism during burn-out. As for a Singapore title, I read Now You See Us, by Balli Kaur Jaswal and was both pleased and mortified to imagine that lots of people around the world are reading this book and learning about the terrible (condescending, elitist, exploitative) ways that migrant domestic workers are treated in Singapore.

Marc Nair, poet, photographer, and educator. My book of the year is Chain-Gang All-Stars, by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah (Harvill Secker, 2023). It is a vicious, viscous takedown of the American prison system, an excoriating look at racialised discrimination through the unseeing eyes of blatant commodification. The combination of injustice and fatalism is a reminder of the darker side of democracy, only somewhat relieved by the gladiators' own arcs of love and redemption. Adjei-Brenyah writes with urgency and anger, fueling his prose with hyperbolic descriptions of the way prison reduces individuals to ratings on a reality show.

Nazry Bahrawi, academic, writer and translator. In this year of grief, I have decided to break Singapore Unbound’s book review rules, a minor transgression in light of the many articles of international law that had been broken with Gaza. My book of the year is a poetry collection not from Singapore, not even from Southeast Asia, but must surely be part of both configurations. I present to you Mural by the late national poet of Palestine Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008), first published in Arabic in 2009 and later translated to English in 2017. The book contains two longform poems, ‘Mural’ and ‘The Dice Player’, both philosophical and poignant, containing multitudes. It also features original illustrations by the late John Berger of the Ways of Seeing fame, a personal friend of Darwish, who had co-translated this collection with Rema Hammami. The two poems show that art can be beautiful even when it is involved, empirical, political, rendering moot the most ridiculous binary of art for art’s sake versus art for society’s sake. That’s a debate for people who have never experienced occupation, nor faced threats of forever expulsion and anytime death. Darwish writes: “I don’t speak or indicate a place / Place is my sin and subterfuge / I am from there.” His uncomplicated but moving words were birthed from a most feared language, a language of terror for some, a language to censure for others. Rendered into the language of former colonialists, these alien words become clear as day, conveying the magnificence of a once grand land and its peoples, now reduced to rubble. They remind us that none of us are free until all of us are free.

Meira Chand, novelist. The Enigmatic Madame Ingram, by Meihan Boey (Epigram Books, 2023). 2023 is the year I discovered a new and powerful young writer in Singapore, Meihan Boey. Her first novel The Formidable Miss Cassidy co-won the Epigram Fiction Prize in 2021 and was the 2022 winner of the Singapore Book Award for Best Literary Work. Her new novel The Enigmatic Madame Ingram, in which Miss Cassidy reappears, follows on from her first. Through the cursed life of young Letty Ingram and her otherworldly mother, the reader enters a local Malay world of mysterious spirits, and immortals like Miss Cassidy, Good battling against Evil, over the millennia. This is difficult material to handle, but in Meihan Boey’s sure hands, The Enigmatic Madame Ingram is testament to her talent, riveting the reader to its strange world until the very last page. Do read it!

Prasanthi Ram, fiction writer. My Book of the Year is the newly released A Man of Two Faces by Viet Thanh Nguyen (Grove Press, 2023). I would argue that Viet is one of the most important and erudite writers of today, and that everyone has to read him at least once. In this eye-opening memoir, he, with both precision and candidness, discusses what it means to be a refugee, and how civilian stories – like that of his family – are war stories too. He also criticises the American Dream as a tool of erasure and a euphemism for colonialism, a thought-provoking stance that is worth ruminating over. If you have yet to discover the phenomenal world that is Viet's writing, I would recommend starting with The Sympathizer (2016), his Pulitzer Prize-winning spy novel set at the end of the Vietnam War, about a half-French, half-Vietnamese Communist spy or sympathizer; on a related note, the book has been adapted into a seven-episode HBO miniseries that is due for release next year. Following which, read this brilliant and emotional memoir. I can guarantee you that your worldview will shift and sharpen for the better.

Ruby Thiagarajan, writer and critic. Perhaps out of unwitting reverence for the written word, authoritarians and their ilk continue to target books. They fear persuasion. They are afraid of the slippery slope that leads from inner transformation to outward change. My book of the year is Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jacquette (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020). The German edition (trans. Günther Orth) is this year's winner of Litprom’s LiBeraturpreis. However, due to a desire to make “Israeli voices especially visible” because “terror can never be allowed to win”, the Frankfurt Book Fair cancelled the award ceremony honouring a Palestinian writer and her novel set during the Nakba and the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine. This episode has eclipsed the reason the book won the award in the first place. It is a tour de force. In detached prose, the first half of the novel recounts the true story of how an Israeli army unit raped and murdered a young Bedouin girl in 1949. The second half follows a woman in occupied Ramallah as she fixates on this event. In just over a hundred pages, Minor Detail demands that the reader reflect on how history is produced and what memory means for the traumatised. I also want to mention Balli Kaur Jaswal’s Now You See Us (HarperCollins, 2023). It is, like all of Balli’s books, tightly plotted and difficult to put down. I don’t know why it didn't receive more buzz here in Singapore. The marketing campaign did it no favours (“Crazy Rich Asians meets The Help!”); I read it as a skewering of Singapore’s shameful record of labour exploitation smuggled in within a charming murder mystery. The detectives here are Filipina domestic workers who must exonerate their friend from the charge of murdering her employer. Many novels would buckle under the weight of the numerous sociopolitical references here but Now You See Us nails the execution. The two books are tonal opposites but I have included them here for the same reason: my admiration for fiction that commits to both an explicitly ethical position and a respect for the form. Us literary types should not kid ourselves. Reading books by and/or about marginalised people, the work of educating ourselves, does little to alleviate the conditions of said marginalisation. But while reading is not a political act, I believe that writing is. The learning still needs to be done.

Yong Shu Hoong, poet and educator. It took a while for me to grab hold of Boey Kim Cheng’s The Singer and Other Poems (Cordite Books, 2022). Initially, I thought perhaps “the singer” might refer to one of Boey’s favourite singers he has collected on vinyl – I’m wondering, Jackson Browne or Zhou Xuan? – but the cover image of an antiquated Singer sewing machine gives the guessing game away. As a fan, I eagerly lapped up poems holding onto his past and parts of Singapore that need to be captured in words before they too disappear; poems about his adopted country of Australia and other stations of arrival and departure; as well as a poem entitled ‘The Middle Distance’ that quotes from Louis MacNeice (“This middle stretch / Of life is bad for poets”) but thankfully is far from “bad”. Be prepared to be charmed by long poems that perhaps recall the ruminations of his non-fiction writing but offer intoxicating ramble to drown in. I’d add that another book I’ve enjoyed immensely is Ethos Books’ reissue of Wong May’s A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals (2023) – not a bad way at all to be introduced to her distinctive poetic style of word play and intriguing enjambments.

Sonny Liew, graphic novelist. Why Don't You Love Me? by Paul B. Rainey (Drawn & Quarterly, 2023). After the relative disappointments of several well-reviewed graphic novels (Daniel Clowes' Monica, Zoe Thorogood's It's Lonely at the Centre of the Earth and Eric Svetoft's Spa amongst these), Why Don't You Love Me was my favourite comic of the year so far, with its narrative mysteries and twists that made you want/need to re-read the whole thing again after it was done. Neil Gaiman's claim in his blurb ("To understand all is to forgive all") perhaps overstates things a little; the ideas explored might not quite hold up upon examination, but the book's ability to compel you to ponder them is testimony to its success.

William Phuan, arts administrator. The Great Reclamation, by Rachel Heng (Riverhead Books, 2023). Sweeping in its scale, intensely intimate in its emotions, The Great Reclamation is arguably the Great Singaporean Novel that we have all been waiting for. The life of Ah Boon, a fisherman’s son, is intertwined with the inexorable progress of Singapore towards self-determination – from the waning colonial days to the Japanese occupation, and to the merger with Malaysia. As he’s caught up in the country’s turmoil, he moves from being a passive witness to a knowing actor in Singapore’s development. The novel adroitly and movingly captures the contradictions of a man – and a country – maturing and growing up, as he navigates between the love of his life, his family and village, and the political ambitions of the Gah men. That Rachel’s book resonates so deeply speaks to not only her skills as a writer and storyteller, but also as a fellow Singaporean who has wrestled with the country’s success and the sacrifices of its people.

From the Singapore Unbound team:

Elise J. Choi, Fiction Review Editor. Rise: A Pop History of Asian America from the Nineties to Now, Jeff Yang, Phil Yu, Philip Wang (HarperCollins, 2022). "A love letter to and for Asian Americans." This accessible tome includes important history lessons as well as entertaining pop cultural nostalgia. I wish I had RISE when I was younger, and I'm glad young Asian Americans have it now.

Jack Xi, Poetry Editorial Intern. The Great Reclamation, by Rachel Heng (Riverhead Books, 2023). Heng's magical realist story of a boy and his fishing village community explores the various forces that shape Singaporean history, land, and identity, culminating in a tragedy that nearly brought me to tears. This is a timely story given Singapore's continued plans for land reclamation, and even if the ocean and magic islands drain out of the middle sections of the book, their eventual return whelms us with full, necessary force. Build Your House Around My Body, by Violet Kuppersmith (Random House, 2021). I first learned about this book during a workshop on the uncanny by Sharlene Teo — the short excerpt we read made me desperate to read more. With this supernatural romp across the history and geography of Việt Nam, Kupersmith unearths the socionatural scars of colonialism and patriarchy, and the terrible bliss of life on the margins... all with a lovingly-rendered air of dread supernatural mystery.

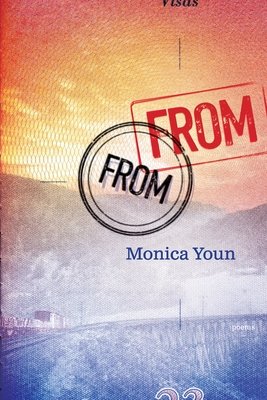

Jee Leong Koh, founder and organizer. The book that has kept me thinking about the formal capacities of poetry to interrogate society and self is Monica Youn’s From From (Graywolf, 2023). It is fierce, intelligent, precise, and vulnerable as it grapples with racial politics in the US from the perspective of a Korean American. My second recommendation is Prasanthi Ram’s Nine Yard Sarees (Ethos Books, 2023). I stand by my blurb for the book: “The madisar, the eponymous nine-yard saree, weaves these stories together beautifully and artfully, these stories about Tamil Brahmin women living mostly in Singapore, but also living, in Prasanthi Ram’s deft, sensitive, and humorous telling, in full, human complexity in their loves and hates, joys and sorrows, envies and regrets. Nine Yard Sarees is an uncommonly rich and precise debut, closely observed, magically empathetic, and formally ambitious.” I’m going to break my own rules by recommending a third book not published in 2022 or 23, but profoundly relevant to these times. Freud and the Non-European (Verso, 2004) is a brilliant reading of Freud’s Moses and Monotheism by the late Edward W. Said. The lecture concludes, “Freud’s meditations and insistence on the non-European from a Jewish point of view provide, I think, an admirable sketch of what it entails, by way of refusing to resolve identity into some of the nationalist or religious herds in which so many people want so desperately to run. More bold is Freud’s profound exemplification of the insight that even for the most definable, the most identifiable, the most stubborn communal identity—for him, this was the Jewish identity—there are inherent limits that prevent it from being fully incorporated into one, and only one, Identity. Freud’s symbol of those limits was that the founder of Jewish identity was himself a non-European Egyptian. In other words, identity cannot be thought or worked through itself alone; it cannot constitute or even imagine itself without that radical originary break or flaw which will not be repressed, because Moses was Egyptian, and therefore always outside the identity inside which so many have stood, and suffered—and later, perhaps, even triumphed.”

Lily Philpott, Program Director. I love Safia Elhillo's raw, tender, and kind poetry collection Girls That Never Die (Penguin Random House/One World, 2022). Reminiscent of the heartbreak and hilarity in your most beloved group chats with the girls who'd never let you down, it's a beautiful exploration of Brown girlhood and the legacies of immigration, at a moment of high risk.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

This Pride month, Ng Yi-Sheng reviews five queer comic titles bringing readers from the Philippines to Indonesia, Japan to Singapore, and to the USA.