#YISHREADS October 2023

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

Halloween's upon us again! But rather than looking at horror fiction, I find myself drawn towards horror non-fiction, i.e. source texts and academic works that try to make sense of the various ghoulies, ghosties and beasties that go bump in the night across Asia.

Included are studies of the pontianak, the hungry ghost, the weretiger, the witch queen Rangda of Bali and a mind-bogging catalogue of monstrosities from India. One caveat: these are mostly authored by Westerners rather than folks from the communities that believe in these creatures. Read with caution—Orientalism is a demon unto itself.

Alluring Monsters: The Pontianak and Cinemas of Decolonization, by Rosalind Galt

Columbia University Press, 2021

I'm cited in this! And I'm excited by this, cos it's probably the most fascinating and thorough study on Cik Pon that I've had the pleasure to read, referencing works I'm familiar and unfamiliar with, plus many friends on both sides of the Causeway: poet Tania De Rozario, activist Thilaga Sulathireh, filmmakers Eric Khoo, Glen Goei and Gavin Yap, artists Tania De Rozario and Yee I-Lann…

What's really cool, however, is that this is specifically media studies—if you wanna see a more anthropological approach to the subject, check out Ad Maulod's thesis “The Haunting of Fatimah Rock”. The book traces portrayals of Miss P from her emergence in the 1950s (did you know actress Maria Menado claimed to have supplied her husband with research while he was writing the script for Dendam Pontianak?) to her late 20th century retreat (did you know Malaysian PM Mahathir Mohamad had a huge vendetta against horror films cos he thought they perpetuated anti-modernity?) to 21st century efforts to reimagine her as a feminist, an anti-racist, an aspiring but imperfect Muslimah, a transmitter of precolonial Malay traditions, a protector of the land.

Now, we all know how the pontianak's paradoxically both a patriarchal symbol of female perversity and a powerful icon of female agency. But Galt expands on this, showing us how she always disrupts gender norms (even in ostensibly antifeminist works—she even proposes the notion of a pontianak feminism!); how she consistently muddles conventions of race, religion and Malay identity. And she ends by challenging the universality of Western film theory by suggesting that Malay animism contributes the perspective that sometimes the POV of the camera is the forest itself.

A helluva book—and also terribly eye-opening to realise how, despite the loss of BN Rao's foundational Pontianak films, how much vintage pontianak media still survives for the intrepid researcher!

Hungry Ghosts, by Andy Rotman

Wisdom Publications, 2021

The core of this book is stories 41-50 of the Avadanasataka, a 2,000 year-old Sanskrit anthology of 100 Buddhist legends. These specific tales focus on the pretas of the title, usually through the narrative of a monk encountering a particularly shocking species of hungry ghost, then going to the Buddha to learn what sins it committed as a human to condemn it to such a fate.

But that takes up only half this volume. The 65-page intro by the translator provides us with a fascinating exploration of the figure of the hungry ghost, not only as seen in these tales, but also in Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, Indian and even 21st century American digital art. He goes into depth explaining his translation of the term "matsarya" as "meanness", i.e. the sin of miserliness and selfishness that gets all these mortals in trouble in the first place.

And (CW: SCATOLOGICAL IMAGERY) he highlights the way these ghosts aren't just portrayed as stinking of shit and looking like shit but also condemned to consume only shit, sometimes because their sin involved tithing monks bowls of shit instead of food, or cups of piss instead of sugarcane juice. Nor is this is a recent perversion: they're present in the actual Sanskrit classic—along with the even more jaw-dropping tale (CW: REPRODUCTIVE HORROR) of a first wife who sabotaged her husband's second wife's pregnancy, thus condemning her to become a ghost who has five babies every day and five babies every night, all of whom she loves dearly, but all of whom she eats, cos there's no other way to slake her hunger.

A few other fascinating things: there's a consistent description of the preta as resembling "a burned-out tree stump, totally covered with hair, with a mouth like the eye of a needle and a stomach like a mountain... ablaze, alight, aflame, a single fiery mass, a perpetual cremation." And it seems there's actually a Flaming-Mouth Ghost King (portrayed on the cover) who appeared before the disciple Ananda, threatening that he will be reborn as a hungry ghost unless he finds a way to feed an infinite number of them—which the Buddha teaches him to do, with a handy rite. There's even sometimes a Queen of the Hungry Ghosts, the goddess Hariti, mother of five hundred sons.

And finally, when we consider the image of the mud-matted, pot-bellied, goitre-cursed, nearly hairless hungry ghosts, invisible to most—might they in fact be meant to represent low-caste untouchables, forced to clear and scavenge human waste, whom upper-castes would've pretended not to see, just as we try not to acknowledge beggars and the homeless ourselves? The paranormal ain't that abnormal, maybe.

Tracking the Weretiger: Supernatural Man-Eaters of India, China and Southeast Asia, by Patrick Newman

McFarland & Company, 2012

I had high hopes for this book: a one-stop reference for lore on the harimau jadian, drawing on disparate Asian traditions from Korea to Sumatra!

But TBH, it falls short. A lot of this is because the author isn't an anthropologist or a folklorist or even literary: he's a medical journalist. As a result, most of the book is just a scrapbook of notes taken from all over the continent, arranged according to loose themes: the menace of tigers, rituals for cohabitation between human communities and tigers, propitiation and appeasement. Which means he's putting examples from Han Dynasty China right next to stories from the British Raj and post-independence Indonesia, with only superficial analysis and synthesis thereof.

What's worse is the fact that a lot of the contents are drawn wholesale from British colonial accounts—huge chunks of Hugh Clifford and other sahibs who positioned themselves as the bringers of civilisation to superstitious natives. True, Newman doesn't present their accounts with total uncriticality, and pretty often their grand schemes of capturing tigers and protecting lives are foiled by the man-eaters themselves. Still, the sheer weight of their colonial perspective ends up making the book a rather unpleasant reading experience. Asian beliefs aren't being mocked, but they are being othered.

Still, this is an informative resource. One of my big takeaways is that us 21st century city people fetishise the untamed sexiness of the tiger without understanding how it preyed on the most vulnerable: babies, children, stragglers in single file processions through the jungle. Ironically, it was usually elderly and sick tigers who became man-eaters (they couldn't catch deer, after all). And weretiger lore often took the form of vicious intra-Asian racism, with Malays constantly suspecting the Negritos and Kerincis, Indians holding the jungle-dwelling Gonds in suspicion (when they were in fact the most vulnerable to attacks).

Also the strange constancy of tropes of weretiger/human marriages (of either gender combination, almost always ending in tragedy and even infanticide), wound doubling and diet doubling (injuries or food ingested in tiger form are sustained in human form), physical deformity (you can tell a weretiger because of his lack of a philtrum, or his hobbled legs, or his tail or lack thereof). And the creepy-as-fuck specific stories of corpses of the slaughtered raising their arms to warn tigers that hunters are nearby (the hunter had to hammer down the arms with stakes to get a good shot); thumb-sized ghosts named bhut riding the foreheads of tigers, directing them. Oh, and common tales of wereleopards too, since they shared similar territory.

So yeah, this is an amateurish scrapbook of a reference text. But the sources are, quite literally, wild.

Rangda, Bali’s Queen of the Witches, by Claire Fossey

White Lotus Press, 2008

This is an MA anthropology thesis, based on the author’s field studies in Ubud in 1999, but it’s a pretty swell read.

Fossey of course recounts the portrayals of Rangda in sculpture and performance, this horrific malevolent entity with glaring eyes, tusked teeth, dangling breasts, garlanded with human entrails; plus her origins in the historical figure of the 11th-century Durga-worshipping widow queen Mahendratta, and the retelling of the legend of her fury on behalf of her spurned daughter Ratna Mengali, and her battle with the holy man Mpu Baradah in the Calonarong dance drama, culminating in her confrontation with the benevolent beast of the Barong.

But she’s also complicating this popular image, noting the oversimplification of Walter Spies and Margaret Mead viewing her as simply the embodiment of all evil, plus her contemporary commodification as a tourist mascot for Bali’s exotica. She’s worshipped in temples (rather like Ravana in Thai Buddhism, who is said to have repented for his sins in the Ramayana), is often invoked to destroy lesser leyaks (witches) and is never killed when she faces the Barong, only made to flee. She thus plays a role in balancing the universe. One account even claims she and the Barong are husband and wife!

Furthermore, through interviews with balians (i.e. shamans), artists (including Murni herself, who kept seeing apparitions of Rangda at night!), curators, her guesthouse operators, even the women in an Internet café, she reveals that there’s no unified vision or opinion of Rangda among today’s Balinese—and perhaps there never was.

One odd topic of debate: is Rangda anti-feminist? There doesn’t seem to be a male counterpart to her (respondents were consistently confused by such a notion), her very name means “widow” and does seem connected to prejudice against older widowed/single women. Fossey’s best riposte to this, other than a WOC-based critique of Western feminism, seems to be that Rangda is consistently performed by men in dance, making her a “false woman”, which hardly feels comforting in an age of TERFism.

Also, a strange revelation that no Balinese women artists had created images of her (as of 2008, to her knowledge)—closest was the Javanese Kartika Affandi, who envisioned her trampling on her own head. Would’ve thought at least one creative woman would’ve yassified this spirit of unbridled feminine rage… but again, that’s probably Western feminism talking.

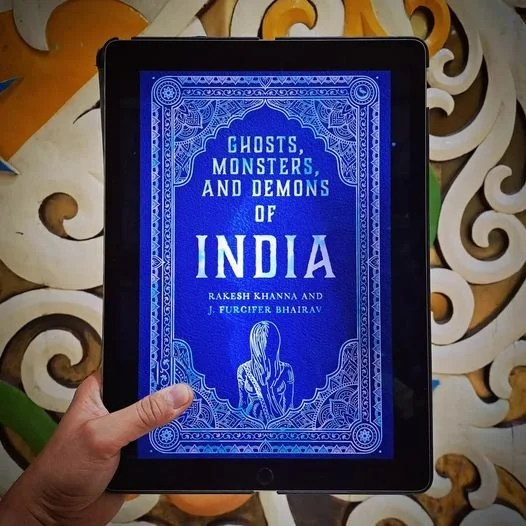

Ghosts, Monsters and Demons of India, by Rakesh Khanna and J. Furcifer Bhairav

Watkins Publishing, 2023

Horror aficionados in Singapore have access to loads of info about Chinese monsters, Malay monsters, Japanese monsters, etc—yet there’s a relative lack of info about South Asian things-that-go-bump-in-the-night: most mythology nerds will only be able to cite fearsome deities (e.g. Kali) and epic demons (e.g. Ravana) rather than what actually scares the average person in the subcontinent.

This book supplies facts in abundance, being an alphabetical cryptobestiary from the Aavi (an incorporeal Tamil spirit of the dead which caught the attention of Helena Blavatsky) to the Zuhindawt (a Mizo spirit that possesses folks and makes them drink piss). What emerges, however, rather than a coherent belief system, is an awareness of the mind-bending diversity of India, with the authors going way beyond Vedic lore to include the traditions of myriad peoples from Tibet, Nagaland, the Andaman Islands; lost myths and medieval Telugu novels and urban legends such as Bullet Baba, a 21-year-old motorcyclist who died in 1991 but keeps reanimating his vehicle, which is now venerated in a shrine; such as Rose, a diligent call centre employee eventually revealed to be the ghost of a woman buried on the grounds of the office block.

What’s also fascinating is the cosmopolitanism of the spirit world, with multi-ethnic ghosts—the Chinkara Bhootas, ghosts of medieval Chinese sailors sunken off the Karnakata coast; multiple British ghosts, including Governor-General Warren Hastings and Major M. Warwick, only revealed upon death to have been the crossdressing widow Mary Warwick; the Kappiri Muthappan, ghosts of African men chained and bricked up alive to guard treasures by the Portuguese—they’re said to smoke cigars, like the Filipino Kapre, and indeed, loads of Southeast Asian parallels are noted, e.g. the Than-Thin Daini of Assam, who resembles the penanggalan/krasue; the Hedali, who resembles the Sundel Bolong.

And of course legions of pontianak-like female vampiric figures, clad in white saris, often with their feet pointing in the wrong direction. (Also, often women become vengeful ghosts when they die virgins! Quite contrary to Abrahamic notions of innocence.)

Khanna and Bhairav go so far as to include ancient Greek tall tales of manticores and unicorns in India; even outright errors like the Farasi Bahari, a merhorse occasionally found in lists of Indian mythical creatures but in fact a term in Swahili for seahorse; misinterpretations of the Anchheri not as an Indian girl ghost from Uttarakhand but an “Indian” ghost from the Chippewa tribe; Western fantasy art portrayals of rakshasas as anthropomorphic tigers thanks to a 1977 Dungeons & Dragons illustration. Comprehensive doesn’t even begin to describe it.

Fair warning, though: it’ll be muddling to read this book from cover to cover like I did. Not just disturbing and disorienting, but also humbling when you realise you know way too little about Indian geography and demographics!

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

This Pride month, Ng Yi-Sheng reviews five queer comic titles bringing readers from the Philippines to Indonesia, Japan to Singapore, and to the USA.