#YISHREADS March 2022

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

I’m a Bookstagrammer: a person who posts pics of the books they read on Instagram. We’re pretty much ubiquitous these days, on and off social media, eyes glued less to the page than to our app activity logs, noses sniffing out cute landscapes to serve as the backgrounds for cover art, fingers ever ready to share expressions of our edgier-than thou-intellectualism.

So why has Jee Leong invited me, of all the influencer-wannabes in the world, to share my mini-reviews in SUSPECT? Partly cos I’m a Singaporean writer, I assume, but also because I’ve been pretty diligently trying to explore the wide world of Southeast Asian literature and history; i.e. while I’m often nepotistically promoting the work of my friends and countryfolk on my platform, I’m also delving into writing from/about Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, etc, and surveying what strange artefacts lie forgotten in our regional archives.

Below I’ve got a selection of stuff I read over the past month or so: some newly published, some out of print, not all of it completely to my liking, critiqued and summarised in a perhaps less than professional style. But it’s all reflective of my current obsessions and curiosities, and I hope you’ll be piqued by at least knowing these books exist.

The Singapore Dilemma, by Lily Zubaidah Rahim

Oxford University Press, 1998

I've had this on my to-read list forever! & wow, this work really goes for the Singapore government’s jugular, pointing out how again & again, they've failed Malay Singaporeans since independence in 1965, especially through their education policy—specifically through their belief in the cultural deficit theory (the same racist thinking that makes folks believe Malay food is unhealthy) rather than realising you've gotta tackle structural/class-based issues before you claim bad maths results are due to race.

Some of this is kinda common knowledge now: the eugenics-obsessed racism of Lee Kuan Yew; the siege mentality of the Chinese in Southeast Asia; the distrust of Malay Singaporeans after Separation. But there's lots of stuff about the 60s-90s that's kinda been forgotten: the fact that there were at one point 13 Malay-medium secondary schools; that the PAP's policies towards Malay education only shifted in the 70s; how the GRC system & HDB racial quotas purposefully destroyed Malay political parties; that Goh Chok Tong threatened Malays in 1988 that "if they commit themselves to another party, they should turn to that party to advance their interests"; how Jufrie Mahmood got accused of being a Malay extremist at the 1991 elections cos he pointed out Malay PAP MPs were kinda rubbish at representing community interests (they also claimed as evidence the fact that he used the phrase "insy'allah").

There are also whole sections dissecting the NEP, the New Education Policy, which gave us things like the Gifted Education Programme/Normal/Express & independent schools. Quite aside from the racial inequities, Zubaidah supplies loads of data on the psychological damage it's caused, plus documentation of the fact that lots of people did object to these new policies. This hits home cos I'm a former GEP kid, i.e. this is the system that made me who I am now.

Plus her prediction that there'll eventually be a time when there's a big enough Malay graduate & intellectual class to call out the regime on their policies, which preach equality while practising elitism of the generationally wealthy, which pretend to multiculturalism while taking all possible steps to preserve majority-race hegemony. I think the time's come now when there's enough folks who can see through the propaganda. This is the woke wave they're afraid of. They taught us language, and our profit on it is we know how to cancel them.

Enrique the Black, by Danny Jalil

Penguin Random House SEA, 2021

I actually read this manuscript ages back, when it was submitted for a competition, and I was floored—this is an epic novelisation of the tale of the Malay sailor, enslaved in Melaka as the property of Magellan and enlisted as a crewman & interpreter on his voyage around the world, only to jump ship in Cebu following his master/enslaver’s death, close to home, making him v possibly the first person to circumnavigate the Earth. Most Malay folks know him as Panglima Awang, after the 1958 novel by Harun Aminurrashid; the author explains how he only heard about him after a mention in Hidayah Amin’s Malay Weddings Don’t Cost $50.

What’s super-interesting to me is how the work works in dialogue with Panglima Awang. Harun imagined the man as an ultimate hero, the pride of the Malay race, already heading a rebel force against the Portuguese in his homeland, making white girls fall in love w him in Lisbon & ultimately arriving home in Melaka where his patriotic warrior girlfriend drops her sword & panties so they can get married immediately. But Danny sees him as a lost kid, gifted with a proficiency for languages (not just Portuguese and Malay, but Chinese and Arabic), but only middling skill at fighting, and not much agency—Lapu-Lapu has to stare him down to remind him that he’s a free man after the death of Magellan. He’s a confused cosmopolitan, just like so many of us today.

Danny’s also able to draw on loads more research about the 16th century than Harun, so we get episodes of him & Magellan fighting a battle in Morocco, trading slaves in Egypt, shifting from Portugal to Spain, enduring the long, mutinous voyage across the Atlantic to encounter Patagonian giants, Chamorro boat-stealers and Antarctic penguins. Special kudos for unflinchingly representing how the sailors have sex w squid and w each other, and Magellan’s brutal punishments for sodomy. (Some historical errors persist, of course: depictions of smoking before the widespread trade of tobacco; the assumption that “Italian” was a language before the 19th century.)

Plus, we get more perspectives than just Enrique’s: Magellan & his bastard son Cristavao; Sultan Mahmud & the Melakan warrior queen Tun Fatimah; Lapu-Lapu, Raja Humabon and his queen Hara Humamay (who’s given more agency than history records); and especially Antonio Pigafetta, as the ship’s recorder, the source for most of this info & a fellow writer.

So why haven’t you heard much about this book since it came out last year? Well, it’s partly cos Penguin Southeast Asia does zero publicity for its authors, but in my humble opinion it’s mostly cos of their non-existent editing policy. Danny’s syntax is occasionally clumsy, even ungrammatical, & for some reason this is a particular problem around the beginning of the book. This’ll be enough to scare most readers off, so they’ll never get to the goosebumps-inducing conclusion. They might also be thrown off by the rapid jumps of perspective, since the copy editor has blithely deleted all the section breaks!

Jit Murad Plays, by Jit Murad

Matahari Books, 2017

This famed Malaysian playwright passed away on 12 February this year at the age of 62. I never met him, though I did see his 10-minute play Malam Konsert (included in this volume) at the Actors Studio in 2003, as well as his cross-border collaboration with Singaporean playwright Haresh Sharma, Separation 40, in 2005.

The accompanying essays in this collection, written by folks like directors Zahim Albakri and Krishen Jit, make it clear what a phenomenon he was when he burst upon the scene: a liberal Anglophone Malay playwright in the 90s & 2000s, confronting taboo subjects like homosexuality & the growing religious intolerance of the first Mahathir era, rejecting old tropes of Malayness in favour of portraying the moral bankruptcy & cosmopolitan confusion of the upper middle-class bumiputeras.

Plus, they're wickedly funny in their portrayal of social mores, e.g. Gold Rain & Hailstones (1993, revised 98) & Spilt Gravy on Rice (2002, revised 03), critiquing anti-hijabi Westernised liberal activists as much as the inheritors of toxic masculinity & generational wealth. My favourite, however, is probably Visits (1993, revised 01), a piece for three women, as vicious in its exposés of patriarchy & privilege as it is inventively hilarious.

Surprisingly, this volume also includes The Storyteller (1996), a musical that was widely panned in its time; the quotes from critics make their disapproval evident. Yet I'm glad it's in here, not just because of the work's subversion of the colonial kampung idyll, but because the actual storyteller's tale within the tale (performed by Jit himself on stage), is Southeast Asian speculative fiction at its finest, w clear callbacks to the folktales of Raja Chulan and Raja Bersiong while also being a heartbreaking allegory for the fracturing of Malaysian society.

Also moving to see how friends of mine—Kathy Rowland, Bernice Chauly, Jo Kukathas—originated these roles, and were part of this exciting new wave of Malaysian theatre history.

RIP Jit Murad. Or, more fittingly for a Muslim: to Him we belong, and surely to Him we shall return.

The Gay Archipelago: Sexuality and Nation in Indonesia, by Tom Boellstorff.

Princeton University Press, 2005.

Damn, this is fascinating: an anthropological study among the gay and lesbi communities of Indonesia (the author writes these terms in italics to emphasise that these subject positions aren't the same as Western notions of gay & lesbian), conducted in Surabaya, Bali and Makassar from the late 90s to the early 2000s.

I bought this book and lost it ages ago, using it as my source for info on historical examples of "queer" identity in the Indonesian islands: the bissu of the Bugis, the warok and gemblak of the Javanese, the 1937 Walter Spies trial. But Boellstorff's actually arguing that these are unrelated to contemporary gay and lesbi identity: his interlocutors often knew nothing of and felt no connection with them. In fact, he couldn't find significant differences btw the communities from various ethnic groups & territories—to be gay or lesbi appears to be a postcolonial Indonesian identity, growing out of the state's emphasis on national unity and heteronormative nuclear families (to the extent that most gay and lesbi he spoke to planned to enter opposite-sex marriages, seeing it as their destiny to reproduce!).

Lots of details about community gatherings (public spaces like town squares & bus interchanges that they occupy, termed "tempat ngeber", often named after foreign locations), gay language (bahasa gay), the dissemination of awareness through print media (the 1981 marriage of two lesbians, Jossie & Bonnie, was covered w great sympathy by Liberty magazine), the tension btw waria (trans woman) and gay, cewek (femme lesbi) and tomboi (butch lesbi or trans man, there's no clear line of division) and the national spread of units of the activist group GAYa Nusantara (which is where the author's concept of the "gay archipelago" originates).

Still, this was published seventeen years ago. Based on my own interactions with queer Indonesians, much has changed, with the rise of violent crackdowns on queer sex and activism. Plus a great quote from a Makassar activist: "Culture is something that is created by humans and then believed. There are people who have created 'gay' here in Indonesia and believe in what they have created. So gay is part of Indonesian culture."

The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, by James C. Scott.

Yale University Press, 2009

Oh man oh man, this is one of those mindf*ck books that really makes you challenge everything you thought you knew about history.

I'd heard the basics before from the YouTube series Crash Course: World History and artist Ho Tzu Nyen's The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia: how there's this huge hilly zone, called Zomia, straddling Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, China, India, etc, that's home to loads of tribal peoples who've historically resisted the reach of state governments: Karens and Shans and Kachins and Hmongs and Miao and Mien & more.

But the book goes further, explaining why they haven't wanted to be under state rule. Scott explains that all the glorious kingdoms we read about in history books, from Chinese dynasties to Bagan and Dai Viet to colonial empires (and yes, postcolonial nations too), have regularly been in the business of enforcing slavery and forced labour & military conscription on their subjects, frequently kidnapping tribal peoples to boost their populations (within a generation or two they usually transitioned from slavery to peasanthood). Irrigated rice farming was prized, not because it's actually better than slash and burn crops and mixed cultivation, but cos it's easy to store and count for taxation, unlike root vegetables which require way less labour.

This is why tribes have repeatedly fled uphill to avoid the abuses of states. And they've been routinely joined by lowland subjects, even Han Chinese like myself, who want out of the state project, regularly absorbing these new populations into their culture. I.e. ethnicities frequently change, whether you're being "civilised" or leaving "civilisation". People don't have ethnicities, Scott says: ethnicities have people.

States have tried to remedy their leakiness through ideology, expounding the evils of barbarism. But these barbarians are often healthier than civilised folks, with mixed diets supplemented by foraging and way less danger of warfare and epidemic disease. Plus, they've adopted their own ideologies, purposefully following different religions from the lowlands (often animist, then in the colonial period Christian, often led by millenarian prophets & rebels), organising themselves in egalitarian systems that make them impossible to control, even, Scott argues, abandoning the use of writing in favour of orality, so that their histories are mutable and dynamic.

And get this: there are lots of Zomias. Folks flee to anywhere that's logistically difficult for armies to follow, whether it's marshlands (e.g. the Great Dismal Swamp which provided refuge for runaway American slaves, or the jianghu of Chinese legend), the steppes (e.g. the Cossacks), the desert (e.g. the Berbers/Amazigh), and the jungles and seas (Scott repeatedly references the Orang Asli and Orang Laut of the Malay world, wishing he could include them in his study as well). Plus a reminder that for most of history, states were outliers, w the bulk of the population living outside them. This was true for a lot of Southeast Asia until maybe the early 20th century. Why can't we start thinking about history this way?

This honestly makes me a little hopeful for the future. They say climate change might make our civilisation collapse; that we'll end up living in barbarian bands again. But that might just be the cycle of history returning us to our natural state. Less glorious, perhaps, but more dignified and equal for a whole lot of people.

Also: now I wanna try reading Kropotkin!

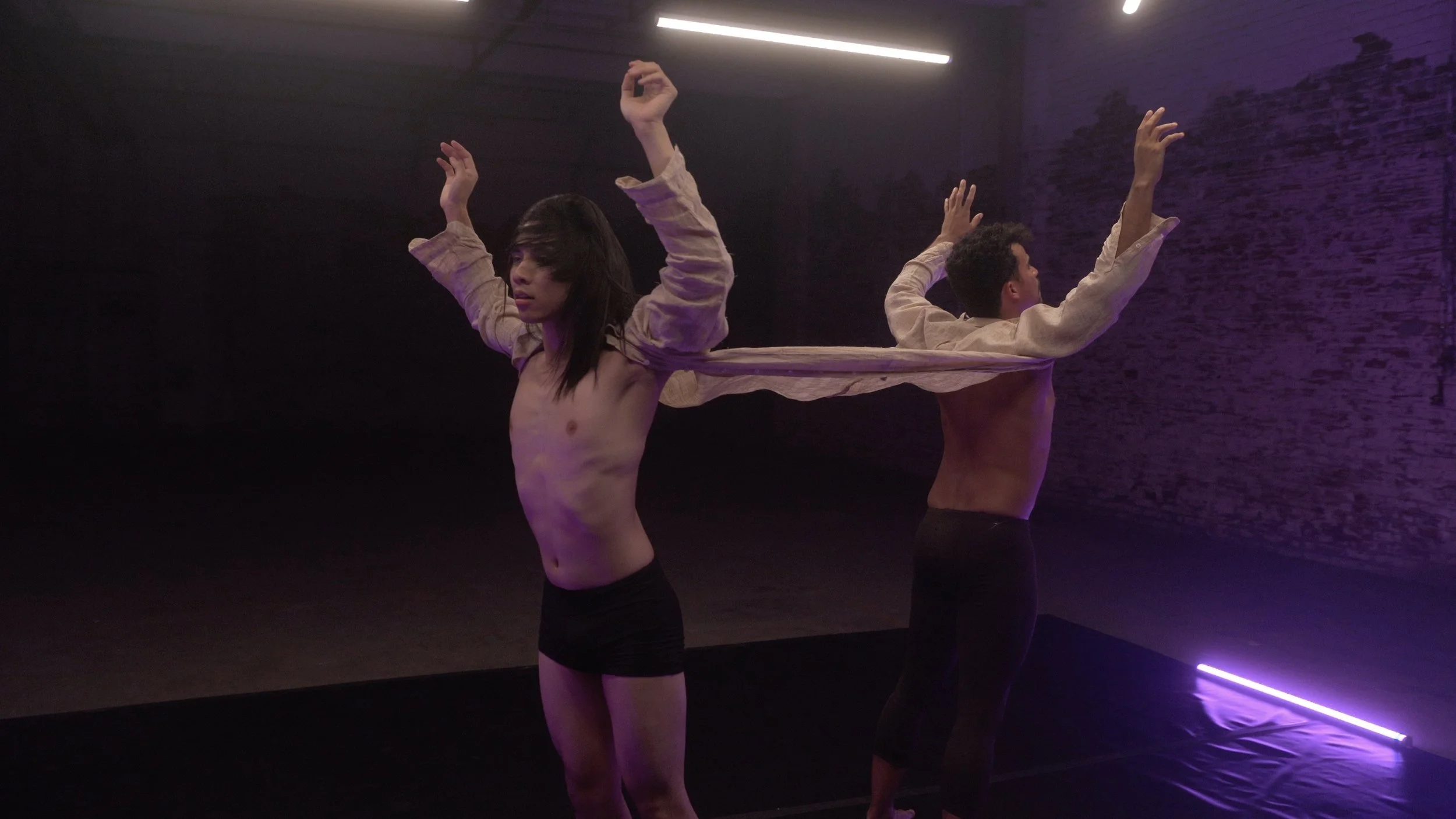

Link to Ho Tzu Nyen's The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia

the critical dictionary of southeast asia (cdosea), by Ho Tzu Nyen, begins with a question: what constitutes the unity of southeast asia — a region never unified by language, religion or political power? cdosea proceeds by proposing 26 terms — one for each letter of the english / latin alphabet. each term is a concept, a motif, or a biography, and together they are threads weaving together a torn and tattered tapestry of southeast asia.

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

This Pride month, Ng Yi-Sheng reviews five queer comic titles bringing readers from the Philippines to Indonesia, Japan to Singapore, and to the USA.