Opinion: Not Nameless. Not Bygones.

Photograph from the Straits Times

Broken bodies. Torn ligaments. Muscle tears. Broken spirit. Fear-filled eyes. Yet another migrant worker has died in Singapore while working or traveling in a lorry to work. Or died from an acute illness. Or killed himself/herself. And tomorrow there could be another one, anyone. One must be careful all the time despite the daily grind—the heat, long hours, fatigue, stress of completing the day’s work, worries about earning enough to pay off recruitment debts, emotional ups and downs in minding a family from afar, blocking out abusive words from supervisors, avoiding the infighting among co-workers—to stay alive, to fulfil dreams of getting out of poverty, sending children to university, and building a house. Must, must work hard. Must, must watch each step. Must, must earn. Dreams cannot die.

But the reality is this—there have been 455 deaths over a period of 22 years (1 January 2000 to 3 August 2022), an average of 20 deaths a year, or close to 2 deaths a month. And there are 173 “unknown” ones—no names in publicly accessible records. A group of volunteers involved in migrant worker development researched the data for more than a year. Compelled by “a desire to commit the names and lives of these workers to a nation’s collective memory,” they combed through public reports of deaths and injuries in Singapore and in the workers’ countries of origin. They collated data on men and women, low-skilled and unskilled. Thoroughness and consistency became a keen focus so that the collated data would be the most reliable statistics on the safety and health concerns of workers who leave their countries to work, legally, in Singapore. Independent media, such as Kontinentalist and Jom, as well as mainstream media have reported on the work done by these volunteers, on what has come to be called, to Singapore’s shame, the Migrant Death Map.

Most members of the total foreign workforce of 1.488 million workers (MOM, June 2023) do go home safely, with enough savings to build lives anew in their own countries. But one too many died at the workplace, from being transported in lorries to work, from illness, from suicide, or from injury sustained in the workers’ dormitory. Many of us are aware that migrant workers die, get injured severely, and face abusive treatment in their work. We hope that the harm is not severe, not frequent, and that the perpetrators will be prosecuted and punished. We are also increasingly aware that the workers’ already-depressed wages go towards paying heavy recruitment debts. Workers take an average of 3.5 years to pay off debts between SGD5,000 and SGD12,000. There are multinational companies that have embraced the Employer Pays Principle, but much work is needed for effective implementation.When a migrant worker dies or is severely disabled, the death or injury affects not only the person but also the family left behind in their country of origin. The family not only loses a loved one and breadwinner but is hounded by ruthless debt collectors for repayment of the recruitment fee. The impact of the worker's death is severe and long-lasting.

A country like Singapore must be expected to look after each and every one of its workers well, to ensure that workers are adequately compensated and safe, as stipulated in national laws and International Labour Organization conventions. Both national and international legislations strongly emphasize occupational safety and health policies and frameworks. The Ministry of Manpower’s own Occupational Safety and Health Division sets itself the goal of reducing “the workplace fatality rate to below 1.0 per 100,000 workers and major injury rate to below 12.0 per 100,000 by 2028.” Such laudatory goals require strong governance, generous resources, and adequate training to be reached successfully. The mental health of workers is a long-neglected issue, but the Covid-19 pandemic has speeded up discussion and action on public policies, support programmes, and resources to attend to mental health.

Nevertheless, it is important to note what international conventions Singapore has not ratified as yet. One specific result of such non-ratification is that weekly rest-days and social-security provisions are still at the discretion of employers. Another result is that there is no protection for whistle-blowers. Even the basic safety of transportation to work is still up for public debate, instead of being ensured by the state. Lorries, which are forbidden legally to carry Singaporeans, are used extensively to carry migrant workers to their worksites. Instead of extending the same protection to migrant workers as it does to its own citizens, the government legislates marginal improvements, such as stipulating more “safety procedures” for riding in lorries, like canopies and higher side railings. The Ministry of Manpower has indeed revised its policy earlier this year—now it asks migrant workers to act as “buddies” to look out for each other’s safety on the roads! Instead of heeding the dangers to workers, the state listens to business interests: switching to buses would increase costs!

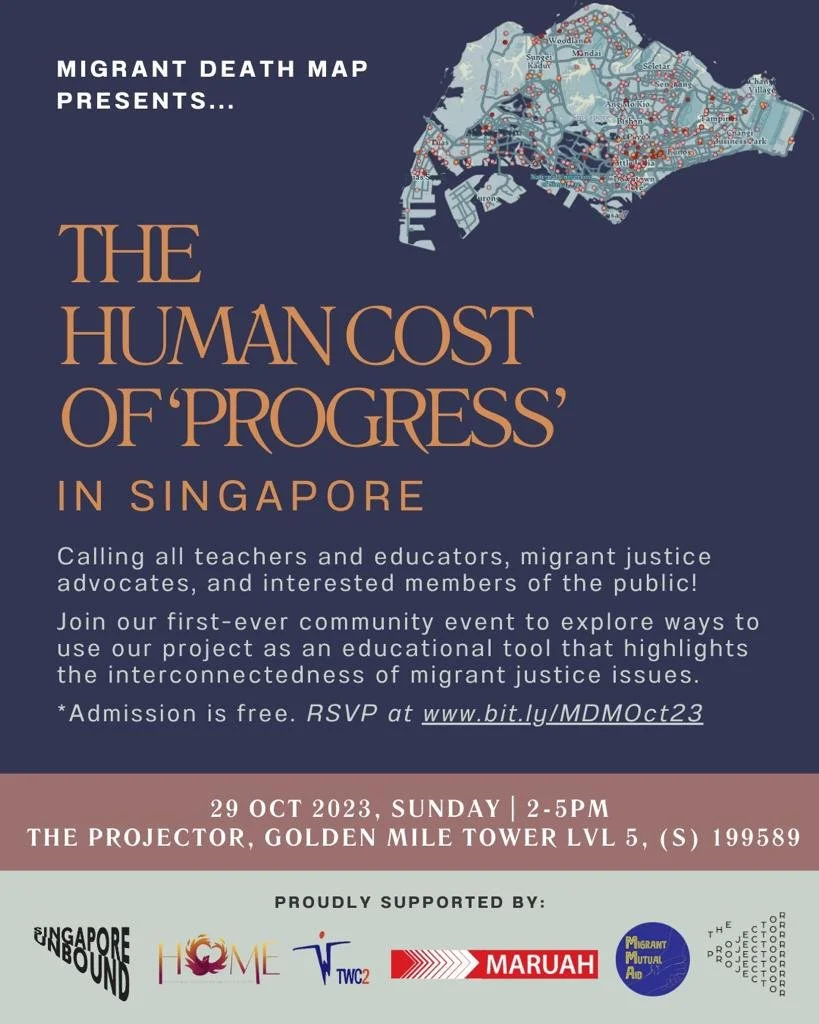

The work for migrant workers’ safety and health is urgent and heavy. Migrant Death Map has its work cut out for it. To move beyond their online work, these dedicated volunteers are hosting a 3-hour workshop called “The Human Cost of Progress” to share their work with educators and the general public. Their first-ever community event will explain their research methods and findings. It will also facilitate an inter-disciplinary discussion on the various intersecting factors behind migrant worker deaths, and breakout sessions on how change and transformation can take place.

"The Human Cost of Progress"

Date and time: Sunday, 29th October, 2-5 pm

Venue: The Projector, 6001 Beach Rd, #05-00, Golden Mile Tower, Singapore 199589

Register: Email the organizers at migrantdeathmap@gmail.com

Singapore Unbound is a proud supporting partner of the community event. We wish the organizers and attendees an inspiring and informative event.

Editorial Board, Singapore Unbound

October 24, 2023

Singapore Unbound is a NYC-based literary organization dedicated to the advancement of freedom of expression and equal rights for all through cultural exchange and activism.

The role of Singapore Unbound’s Editorial Board is to provide readers with a thoughtful and independent perspective on issues that resonate with our organization’s values. The Board also seeks to engage readers in a critical dialogue about important social questions by providing them with the information to make decisions and take actions for the common good.

The Editorial Board develops its positions on a variety of issues, but the views expressed are independent of the rest of the organization. Editorials are unsigned to reflect the fact that they represent the collective views of the Board instead of any individual member.